- What is Epilepsy?

- What is a Seizure?

- Causes

- Diagnosing Epilepsy

- Epilepsy Syndromes

- Lobes of the Brain

- Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures

- Seizure First Aid Video

- Seizure Types

- Status Epilepticus

- SUDEP

- Treatments

- Triggers

What is Epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a condition of the brain characterized by recurrent seizures. Approximately one in ten Canadians will experience at least one seizure during their lifetime. One seizure does not necessarily signify epilepsy (up to 10% of people worldwide have one seizure during their lifetime) (World Health Organization). Epilepsy is a condition defined as multiple seizures starting in the brain. Epilepsy can present at any age, although its onset is most often in childhood or in the later years of life. Sometimes those who develop seizures during childhood outgrow their seizures. In the elderly, there is an increased incidence due to strokes and aging of the brain. In more than half of those with epilepsy, seizures can be well controlled with seizure medication.

- Approximately 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological diseases globally.

- The brain is made up of billions of nerve cells or neurons that communicate through electrical and chemical signals.

- Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic neurological disorders.

- In North America, almost four million people have epilepsy.

- An estimated one percent of the general population has epilepsy. Based on that estimate, 330,000 people in Canada have epilepsy.

- When there is a sudden excessive electrical discharge that disrupts the normal activity of the nerve cells, a seizure may result.

Reprinted in part from Living with Epilepsy (Epilepsy Education Series, Edmonton Epilepsy Association)

What is a Seizure?

The brain is made up of billions of nerve cells or neurons that communicate through electrical and chemical signals. When there is a sudden excessive electrical discharge that disrupts the normal activity of the nerve cells, a change in the person’s behaviour or function may result. This abnormal activity in the brain that results in a change in the person’s behaviour or function is a seizure.

Anyone can have a seizure. In fact, approximately one in ten people in Canada will experience at least one seizure during their lifetime. One seizure does not necessarily signify epilepsy (up to 10% of people worldwide have one seizure during their lifetime). Epilepsy is a condition that is defined by multiple or recurrent seizures. Approximately 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological diseases globally.

A seizure may take many different forms including a blank stare, muscle spasms, uncontrolled movements, altered awareness, odd sensations, or a convulsion. The form the seizure takes depends on where in the brain the excessive electrical activity occurs.

Sometimes the form of a seizure can be mistaken by others to be deliberate acts. Sometimes people misunderstand seizures and think that those with epilepsy are mentally disabled or are more likely to be violent. Seizures are not deliberate acts and people living with epilepsy are not prone to violence.

An excessive electrical discharge in the brain temporarily causes a change in the person’s function or behaviour. When the seizure is over, the person typically returns to normal.

Reprinted in part from Epilepsy: Seizures & First Aid (Epilepsy Education Series, Edmonton Epilepsy Association) and World Health Organization

Causes

Epilepsy is caused by a number of factors that affect the brain. The cause of epilepsy is sometimes genetic and sometimes acquired but often both factors play a role.

The causes vary according to the age of onset. Seizures are classified as symptomatic, in which the cause is known, or idiopathic, in which the cause is unknown. In approximately 60 to 75 percent of epilepsy cases, no specific cause of the seizures can be identified. In the remaining 25 to 40 percent, the causes may include:

- Genetic causes

- Birth injury (e.g. lack of oxygen to the brain at birth)

- Developmental disorder (e.g. brain damage to the fetus during pregnancy)

- Brain trauma (e.g. from car accidents or sports injuries)

- Infection (e.g. meningitis, encephalitis, AIDS)

- Brain tumour

- Stroke

- Cerebral degenerative disorder (e.g. those associated with Alzheimer’s Disease)

- Substance abuse

Is Epilepsy Hereditary?

Some types of epilepsy have a genetic basis. In certain epilepsies, one or more inherited genes may result in the disorder. In other cases, an inherited neurologic disorder that involves structural or chemical abnormalities in the brain can increase the risk of seizures and lead to epilepsy.

Another factor associated with a genetic cause of epilepsy is an inherited susceptibility to seizures. Each individual has a seizure threshold that determines the level at which the brain will have a seizure. Some individuals inherit a lower threshold or lower resistance to seizures resulting in a greater risk of having seizures.

The risk of a child having unprovoked seizures is one to two percent in the general population and approximately six percent if a parent has epilepsy.

Reprinted in part from Living with Epilepsy (Epilepsy Education Series, Edmonton Epilepsy Association)

Diagnosing Epilepsy

An EEG is a painless, non-invasive test that looks at the patterns and location of electrical activity in the brain and usually takes less than an hour. The electrical impulses of the brain are recorded by small metal electrodes placed on the person’s scalp, connected through wires. Although an abnormal EEG result can confirm a diagnosis of epilepsy, a normal EEG result does not rule out the presence of epilepsy.

What does an EEG tell us?

“Epileptiform abnormalities” or “epilepsy waves” look like spikes. Certain patterns show a tendency toward seizures. Spikes and sharp waves measured by EEG in a specific area of the brain can indicate the origin of one’s partial seizures. Sometimes, abnormal patterns may be seen on an EEG due to conditions other than seizures, such as brain tumour, stroke, or head trauma.

How to prepare for an EEG and what can you expect?

1. Before EEG

- Wash hair without conditioner or gel.

- Follow the instructions given for what to eat or drink before EEG.

2. During EEG

- A mild sedative may be given to restless patients.

- A hospital clothing or a gown may be given.

- You may be required to lie down or sit.

- Your head will be measured and marked with a wax pencil to know where to put the electrodes.

- The marked areas on your head will be cleaned with a thick soap.

- Electrodes will be temporarily stuck to your head with cream and gauze.

- Sometimes the electrodes are in a rubber cap like a bathing cap.

- Throughout the test, the machine makes a continuous record of your brain activity, or brainwaves, on a long strip of recording paper or on a computer screen.

- The technologist may ask you to do certain exercises to stimulate certain types of brain activity. These activities will not always trigger seizures. Examples include:

- Breathe deeply for three minutes (hyperventilation)

- Open and close your eyes

- Watch a flashing bright light for a few minutes (photic stimulation)

- You may have the test while you are asleep and then again while you are awake. This is done to see the differences in the brain when you are awake and asleep.

3. After EEG (Side Effects)

- Your hair may be a little sticky from the cream. You can easily wash out the cream with shampoo.

- If a sedative was used, the patient may be sleepy, grumpy, and unsteady for four to six hours. You need to be monitored for about six hours after the EEG test. Patients should only have small amounts of clear liquids such as water or apple juice. When they are fully awake, regular meals and activities may be resumed.

Types of EEG Testing

Sleep-deprived EEG

The clinician may ask that you be sleep-deprived before an EEG. Abnormal brain activity may be easier to see when you are tired or falling asleep.

Video-EEG

A video-EEG test records your brainwaves on an EEG and records the patient on a video camera. The purpose is to be able to see what is happening when you have a seizure or event and compare the picture to what the EEG records at the same time. By doing this, doctors reading the EEG can tell if the seizure or event was related to the electrical activity in the brain. If so, we’d call this an epileptic seizure. It is helpful to determine if seizures with unusual features are epilepsy, to identify the type of seizures, and to pinpoint the region of the brain where seizures begin. Other names for video-EEG tests include: EEG telemetry, EEG monitoring, or video-EEG monitoring. Usually, these terms mean the same thing.

Ambulatory EEG units

These units are sometimes used to monitor a person for longer periods of time. The individual wears a portable EEG unit that records brain activity during normal activities at home, at work, or during sleep.

Partially reprinted from Sick Kids, Elizabeth J. Donner, MD, FRCPC, 2/4/2010

INTRACRANIAL ELECTRODE IMPLANTATION

EEG scalp recording cannot always identify the exact location of where a seizure starts. Some people will need further testing, which can be done using intracranial electrodes such as subdural, grid, or depth electrodes. Surgery is needed to put these special electrodes in place. Your neurologist and neurosurgeon will discuss all options and information about the surgery with you prior to the operation.

Types of Electrodes

- Intracranial electrodes: are EEG electrodes that are placed inside the skull to monitor seizure electrical activity in the brain as precisely as possible.

- Subdural electrodes: or grids are plastic strips or sheets with electrodes embedded on them. They are placed directly on the brain.

- Depth electrodes: are thin, wire-like tubes with metal contacts. These are inserted into the brain.

The Surgery

Electrodes are inserted while you are under a general anesthetic and are sleeping. During the procedure, your hair may be shaved off and your scalp will be cleansed with a special orange solution called betadine. The neurosurgeon will insert the electrodes using different surgical techniques. Subdural electrodes are inserted through small nickel-sized holes that are drilled through the skull. The location and number of the holes will depend on the type of seizures and what questions need to be answered. Generally, 2-4 holes are required and several electrodes may be placed through each one. Depth electrodes are individually inserted through tiny holes in the skull. Grids are inserted by removing a section bone from the skull (an opening called a craniotomy), placing the grid on the brain, and then replacing the bone. After the surgery, you will go to the post anesthetic care unit (PACU) for monitoring until you wake up. Before going to the epilepsy unit, you will go for a CT scan and/or MRI to ensure the electrodes are in place. The electrode wires are stitched to the scalp and incisions in the scalp are closed with staples. A large, bulky dressing is applied over the wires. You might have drainage onto this dressing for the first few days after surgery. If there is a large amount, nurses will reinforce the dressing and keep the head of your bed at a 30-degree angle. The dressing will be changed at the surgeon’s discretion. At that time, the surgeon may examine the incisions for redness, infection, or leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Nurses will assist the neurosurgeon in this process, which is done on the epilepsy unit with curtains drawn for privacy.

Post-Operative Care

After surgery, you will be offered medication for pain and nausea. In addition to being monitored for seizure activity, your neurological condition will be checked very carefully by the EMU nurses. You will have an intravenous (IV) infusing after the surgery to help keep you hydrated. The IV will be discontinued once you are eating and drinking well. It is highly encouraged that you begin to resume your normal activity levels after surgery to promote your health and healing. You are still permitted to leave the floor 3 times a day, for a maximum of 15 minutes each time. Please ask a nurse to disconnect you when you wish to leave the unit.

Removing the Electrodes

Once the neurological team is satisfied with the EEG recordings from your seizures, the neurosurgeon will remove the electrodes. Removing subdural or depth electrodes is a simple procedure done in the treatment room while you are awake, and grid removal is done under general anesthetic in the operating room. You will be discharged the next day. Nurses will explain and provide instructions for your discharge. A follow-up appointment with your family doctor is needed to remove any sutures. You will also receive a follow-up appointment with your neurologist/neurosurgeon. It will take about 6 months to 1 year for the bones to heal from the holes or craniotomy. Scalp incisions will heal in 10 days. If you have any questions or concerns you can speak to a nurse, neurologist, neurosurgeon, or another member of the health care team at any time.

SCALP EEG LEADS IN THE EPILEPSY MONITORING UNIT

To monitor your brain activity, the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit (EMU) uses EEG (electroencephalogram) leads that are glued onto your scalp.

How are the leads used?

Your EEG leads will be put on by the EEG technologists. They will apply and remove wires, and also test the system to make sure that everything is working. When the leads are on your scalp, they will then be connected to a small, portable recording unit called a head box. This sends information about your brain waves to larger units on the wall using a connecting cord.

Disconnecting from the wall unit

You can disconnect the cord from the wall computer as necessary; for example, if you need to go to the bathroom or to shower. You can also leave the unit up to 3 times a day and for 15 minutes each time, which is how long the head box’s memory will last without being plugged in. It’s important to remember to plug your head box back in after you disconnect it. This is so computers record as much of your brain activity as possible. Every day, the doctors will review the activity that is recorded.

Routines

Every 5 days, the leads will be temporarily removed so you may wash your hair. EEG technologists will also perform tests (called awake triggers) during the day where you will be asked to lie down with your eyes closed for 10 minutes. At night, nurses will record sleep triggers.

Monitoring Devices

Along with the EEG leads, we use other devices to monitor you. There are video cameras and microphones as well as infrared light cameras above each bed. Using these, the doctors can have visual and audio information to compare to what they see on the EEG recordings.

What are MRIs?

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is a way to take pictures of your body to look at the structure and features.

- The machine uses a magnetic field, which is why it is important to remove all metal from your body (such as piercings and jewelry) before you go for testing.

- On the EMU, MRI’s are most often used to look at your brain to help provide a better understanding of how things look.

EEG leads and MRIs

- The EEG leads are MRI compatible, which means that you don’t need to have them removed if you are sent to an MRI.

- However, it’s important to know that the leads are manmade and there is a small chance of an electrical current being produced in the wire. This can heat the leads up and create the small chance of a burn. This is not common, but if your leads feel warm or unusual in any other way during your MRI, be sure to alert the MRI technologist immediately.

Important Information

Please do not chew gum while on EEG monitoring because it disturbs the normal recording of your brain activity. If you experience any questions or concerns, you can speak to a nurse, technologist, or another member of the health care team at any time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is my head itchy?

The conductive gel used on the EEG leads that allows them to record well eventually dries, and this can make your head itchy. If this occurs, ask the nurses for an antihistamine such as Benadryl.

How long do I keep these leads on for?

The EEG leads stay on for the duration of your time at the unit, but they may be removed periodically.

Can I take them off?

Your leads will be removed by EEG technologists every 5 days so you can have the chance to wash your hair.

Can I shower?

You can shower with the leads on, but it is important to keep water away from them. Please ask your nurse to disconnect the leads before you go into the shower.

Can I leave the unit?

You can leave the unit 3 times a day for 15 minutes each time by signing out at the nurse’s station. Note: Smoking cessation aids are available to help smokers stay within these limits.

Epilepsy Syndromes

A person’s epilepsy may be categorized into a specific type of epilepsy syndrome. Each epilepsy syndrome is characterized by specific seizure type(s), typical age of onset, predictable EEG pattern and other common traits. When an epilepsy syndrome is identified, it helps with understanding the probable causes (etiologies) and determining the ideal type of anti-seizure medication(s).

Reprinted from International League Against Epilepsy, Epilepsy Syndromes

Aicardi's Syndrome

Overview

Aicardi’s Syndrome is only seen in girls, and usually appears in the first year of life. It is caused by an abnormality in the development of the brain prior to birth. Aicardi’s Syndrome is rare and does not run in families. The long-term prognosis is poor with reduced life expectancy due to severe seizures and other physical problems.

Symptoms

- Epilepsy early in life, usually starting with infantile spasms, with the possibility of progressing to other types of seizures

- Other abnormalities may be present, including those of the spine, facial characteristics, or of the heart.

- Developmental delays from an early age. Stiffness or extreme weakness of one or more limbs.

- Learning difficulties are always present and usually severe. Limited language and social development.

- Eye problems are prevalent. Abnormalities known as Lacunae and unusual eye movements are common and occur because the retina has not developed properly. Vision is usually impaired but blindness is uncommon.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for Aicardi’s Syndrome as a whole. Treatment involves attempting to minimize symptoms through anti-epileptic drugs, physiotherapy, and other emotional and medical supports used to treat a child with multiple disabilities.

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy

Overview

Benign Rolandic Epilepsy is also referred to as ‘benign partial epilepsy of childhood’ or ‘benign focal epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes and is one of the most common types of epilepsy in children; about 15-20%. It is known as benign because of the high probability that it will be outgrown during puberty. By age 14, 95% will have undergone permanent remission. It affects boys and girls equally.

Symptoms

- Seizures often start upon the child beginning to wake up or during sleep.

- Begins with a tingly sensation on one side of the mouth and may involve the throat which can garble speech and make the child hard to understand. May make gurgling noises and drool substantially.

- Seizures may cause twitching movements and stiffness on the side of the face being affected, and may then spread to the rest of that side of the body.

- Sometimes the seizure will spread to the whole body, causing a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. The child will become unconscious, fall to the floor, and body and limbs convulse and jerk.

Treatment

Often children with Benign Rolandic Epilepsy do not need treatment at all. If treatment is required, anti-epileptic medications are most often used, which may limit or eliminate the seizures entirely. Benign Rolandic Epilepsy responds well to treatment.

Childhood Absence Epilepsy

Overview

Childhood absence epilepsy is a genetic generalized epilepsy that should be considered in an otherwise normal child with multiple daily absence seizures. The prevalence is only slightly higher for girls than for boys. Intelligence is not affected, with some studies actually showing children with this syndrome as having IQ scores 10% above normal. In most cases, the absences will stop at puberty. However, in about 20% of cases, other types of seizures will start and continue on into adulthood.

Symptoms

- Sudden onset of absence seizures can last generally between 4 and 20 seconds. These seizures can occur many times daily.

- Seizures tend to appear in groups of seizures or clusters.

- They may present as only a loss of awareness or may include actions such as a fluttering of the eyelids, loss of muscle tone, eye-rolling, and rapid pulse.

Treatment

Seizures are controlled with anti-epileptic medication, which is successful in most cases.

Febrile Seizures

Overview

Febrile Seizures are not considered to be epilepsy. They occur in children and infants whose temperatures have been elevated due to some infection in the body. Thirty to forty percent of children who have a febrile seizure will experience some sort of recurrence. However, only three percent will develop epilepsy during childhood.

Symptoms

- A generalized convulsive episode involving a trembling or shaking of the body and limbs. May be only slightly visible in some instances.

- Risk factors that may indicate the subsequent presence of epilepsy include:

- A prolonged seizure lasting more than 15 minutes

- Recurrence of further seizures within a 24 hour period

Treatment

In most cases, physicians do not prescribe the long-term use of anti-epileptic drugs for febrile seizures. Instead, the fever itself may be treated in an attempt to lower the body temp and, in turn, control the seizure. Children prone to febrile seizures may be treated at the time of the seizure with an oral or rectal treatment.

Infantile Spasms/West's Syndrome

Overview

Although West’s Syndrome and Infantile Spasms are not exactly the same thing, they have come to be used interchangeably because one almost always accompanies the other when it develops in children. This type of epilepsy occurs in about 1 in every 2000-4000 children and usually appears in the first 3-6 months of life at which point development usually halts or regresses. Eighty-five percent of children who will develop it will do so before the age of 12 months.

Symptoms

- Characterized by three recognized features: spasms, mental retardation, and chaotic brain activity on the EEG (hypsarrythmia).

- The spasms appear as sudden contractions lasting 2-10 seconds and can include stiffening of the body or arching and extending action of body, arms, or legs.

- Spasms usually occur in a series of several in a row and the series usually abates within 10-30 minutes.

Treatment

Treatment is typically anticonvulsants or steroids, with the AED vigabatrin (Sabril) being most effective, but used with caution due to its permanent effects on vision. The outcome is variable and depends mainly on the cause of the syndrome.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

Overview

Also known as Janz Syndrome, Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy can occur anytime from age 8 to 30 but usually develops during or shortly after puberty. It accounts for 8-10% of all epilepsies of adulthood and adolescence.

Symptoms

- Characterized by myoclonic episodes or sudden jerking movements frequently occurring in a series or upon waking. In the majority of cases, they are followed by a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. In some cases, absence seizures will also be a part of the syndrome.

- Photosensitivity among people with Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy is relatively common.

- Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy is adversely affected by an irregular lifestyle, and seizures may be triggered by such things as sleep deprivation, irregular sleep times, alcohol/drugs, menstruation, stress, and strong emotional reactions.

- Seizures tend to last throughout life but with treatment may subside somewhat in mid-adulthood.

Treatment

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy appears to be easily controlled with medication and lifestyle adjustment with over 80% of patients achieving seizure control. However, relapse is common especially with some deviation from a healthy, regular lifestyle, or from withdrawal from the anti-epileptic medication.

Landau Kleffner Syndrome

Overview

Also known as ‘Acquired Epileptic Aphasia in Childhood’, Landau Kleffner Syndrome is a relatively rare disorder which develops in children usually between the ages of 3 and 7 years old while a child is developing their language recognition and abilities. Twice as many boys are affected than girls.

Symptoms

- The first indication of Landau Kleffner Syndrome is the developed inability in children to speak. The child will show difficulty in understanding what is said to them, as well as the ability to put their own thoughts into words.

- Seizures will usually follow within a few weeks of the development of the language problems and can include both tonic-clonic and complex partial seizures.

- Rarely, a severe behavioural disorder with autistic and psychotic features may develop.

Treatment

Landau Kleffner responds well to anti-epileptic drugs and the long-term outlook for this disorder is a positive one. As well, a careful assessment of the child’s educational strengths and needs is very important so that appropriate educational supports can be put in place during this time. For the vast majority, the seizures will usually disappear by the time they reach their mid-teens. Language skills usually improve over time, but are less predictable and may need additional support.

Lennox Gastaut Syndrome

Overview

Lennox Gastaut Syndrome is one of the most severe of childhood epilepsy syndromes. It accounts for anywhere between 3 and 10% of all childhood epilepsies and usually develops between the ages of 3 and 5 years. About 20% of all cases develop from previous West’s Syndrome. While the cause is often unknown, Lennox Gastaut can develop from several known causes:

- developmental malformation of the brain

- brain disease such as tuberous sclerosis

- brain injury relating to problems with pregnancy and birth

- severe brain infections such as meningitis or toxoplasmosis

Symptoms

- Characterized by very frequent seizures of several different types. Most common are drop attacks, atypical absence seizures, and tonic seizures. However, other types can occur.

- Some children with Lennox Gastaut are known to be prone to non-convulsive status epilepticus which requires immediate emergency intervention.

- Lennox Gastaut affects intellectual development to varying degrees, with some children being dependant on a caregiver for many or most of their activities.

Treatment

Unfortunately, this syndrome seems to be very difficult to treat and often does not respond to typical epilepsy medications or will respond for a brief time only. A small percentage of people with this syndrome will outgrow their seizures and attain normal or near-normal intelligence and abilities. For others, treatments such as the ketogenic diet, vagus nerve stimulation corpus callosotomy surgery have been utilized with varying degrees of effectiveness.

Rasmussen's Syndrome

Overview

Also known as Rasmussen’s encephalitis, this syndrome is a very rare form of brain malfunction that may begin at any time in childhood. The brain cells in one hemisphere of the brain become inflamed, the cause of which is not yet determined.

Symptoms

- Resulting from the inflammation, the nerve cells of the brain malfunction and fire off electrical activity which in turn causes epilepsy.

- Typically causes partial epilepsy which becomes continuous. This is evident with simple partial motor seizures causing rhythmical jerking of the arm or leg on the opposite side of the body as the inflamed brain cells.

- Can lead to irreversible damage of the nerve cells caused by the inflammation and atrophy of the brain.

Treatment

After a period of some years, this inflammation and deterioration usually stop of its own accord. However, nerve cells that have already been injured cannot regenerate. In some instances, some treatment may be afforded through brain surgery to remove the affected area of the brain if this is feasible. Also as a result of the learning difficulties caused by the inflammation, careful educational and social supports should be implemented to facilitate learning.

Reprinted in part from epilepsymatters.com and ILAC.

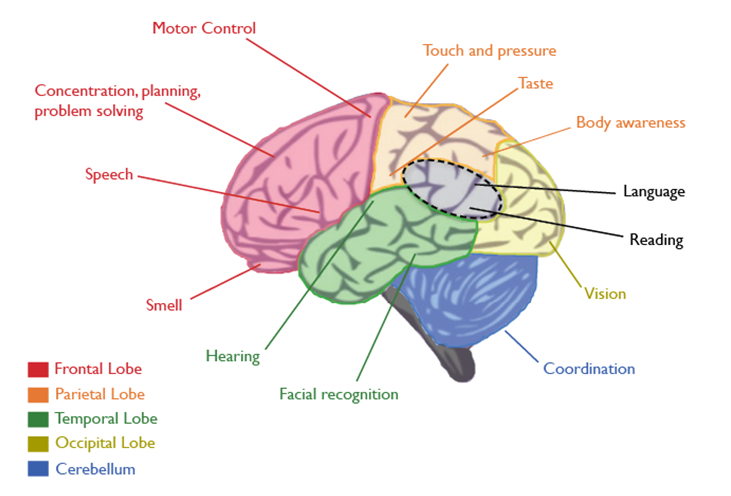

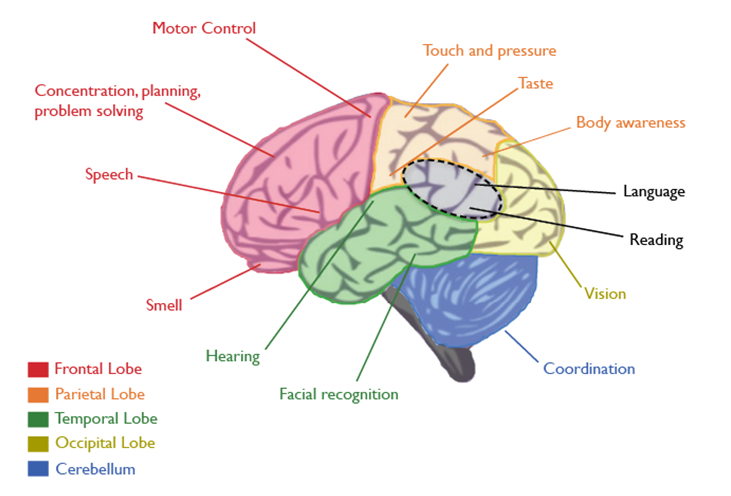

Lobes of the Brain

Epileptic seizures start in the brain. The area or lobe of the brain in which they occur can determine how they will affect a person’s body. Here are some of the ways that seizures in different lobes can affect your mind and body. This table shouldn’t be used to diagnose epilepsy. It simply provides information to help you understand your seizures.

Lobes of the Brain and the Symptoms they Trigger

FRONTAL LOBE

The frontal region of this lobe is called the prefontal cortex. It is involved in planning, organizing, problem-solving, attention, personality, and a variety of “executive functions” including behaviour and emotions. Motor function, including the coordination of mouth and tongue movements for speech, as well as movements of all body parts, are managed by the frontal lobe.

A seizure in this lobe of the brain may cause:

- Inability to move certain parts of the body

- Inability to speak

- Working memory deficits

- Personality and mood changes

- Executive function deficits (such as trouble focusing, difficulty planning, difficulty with problem-solving)

- Difficulty switching strategies when a situation changes

PARIETAL LOBE

The parietal lobes contain the primary somatosensory cortex which controls sensation (touch, pressure). Behind the primary somasensory cortex is a large association area that is involved in the judgment of texture, weight, size, shape of objects.

A seizure in this lobe of the brain may cause:

- Difficulty drawing objects

- Difficulty distinguishing left from right

- Difficulty with mathematics

- Lack of awareness for certain body parts and or space

- Difficulty with hand-eye coordination

OCCIPITAL LOBE

The region in the back of the brain processes visual information.

A seizure in this lobe of the brain may cause:

- Visual deficits

- Visual illusions

- Deficits in colour perception

- Deficits in movement detection

TEMPORAL LOBE

Like all lobes of the brain, there are two temporal lobes (one on each side of the brain) located at about the level of the ears. These lobes allow a person to tell one smell from another and one sound from another. They also help in sorting new information and are believed to be responsible for short-term memory (i.e., memory for pictures and faces). Specifically, the left lobe of the brain is mainly involved in verbal memory (i.e. memory for words and names).

A seizure in this lobe of the brain may cause:

- Difficulty recognizing people or places

- Difficulty understanding speech and language

- Difficulty producing coherent speech

- Difficulty identifying and naming objects

- Interference with long-term memory

- Increased or decreased interest in sexual behaviour

- Inability to categorize objects

INSULA

The insula plays a role in processing certain types of sensory information – such as taste. Pain and temperature, sensory information from the digestive system, as well as certain components of auditory information, are also processed by the insula.

A seizure in this lobe of the brain may cause:

- Language deficits

- Visual illusions

- Inability to recognize sounds

- Deficits in taste perception

This information should not be used for diagnosis. Reprinted from Brain Matters: An Introduction to Neuroscience (Epilepsy Southwestern Ontario).

Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures

Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures (PNES) are not classified as a form of epilepsy. They affect between five and twenty percent of people thought to have epilepsy. Psychogenic seizures can occur at any age but are more common in people under the age of 55. They occur three times more frequently in women than men. They may arise from various psychological factors, maybe prompted by stress, and may occur in response to suggestion.

Such disorders seldom occur in the absence of others. Trauma related to physical illness has been found to trigger these seizures in elderly individuals. People with early-onset psychogenic seizures often have a history of sexual abuse.

How it Affects People

Psychogenic seizures can be characterized by features common with epilepsy like writhing and thrashing movements, quivering, screaming or talking sounds, and falling to the floor. Psychogenic attacks differ from epileptic seizures in that out-of-phase movements of the upper and lower extremities, pelvic thrusting, and side-to-side head movements are evident. However, psychogenic seizures vary from one occurrence to another and are not readily stereotyped.

Indicators like pupillary dilation, depressed corneal reflexes, the presence of Babinski responses, autonomic cardiorespiratory changes, tongue biting, and urinary/fecal incontinence are more probable with epilepsy. These are not usually manifested in psychogenic seizures.

Psychogenic seizures may last a couple of minutes or hours, ending as abruptly as they began. A person may experience anxiety prior to an attack, followed by relief and relaxation afterward. This leads some to postulate that psychogenic seizures may occur as a direct response to stress in order to relieve tension. Afterward, patients usually have a vague recollection of the seizure, without the usual postictal symptoms of drowsiness and depression.

It is difficult to differentiate between psychogenic and epileptic seizures. One highly reliable indicator of a psychogenic seizure is eye closure during the seizure. When people with epilepsy have seizures, the eyes tend to remain open. Still, in 20 to 30 percent of cases, epileptologists are incorrect in attempting to distinguish one from the other.

Misconceptions

Although psychogenic seizures are not caused by electrical discharges in the brain and thus do not register any EEG abnormalities, they are often mistaken for epileptic disorders. It is also possible to have both psychogenic seizures and epilepsy. Most patients with psychogenic seizures are misdiagnosed and consequently treated with epilepsy drugs or other epilepsy therapies, sometimes with severe and fatal side effects.

Medications are ineffective in the treatment of psychogenic disorders. Patients who are diagnosed with psychogenic seizures are usually referred to a therapist to learn to control stress and become familiar with coping techniques. As the vast majority of psychogenic seizures operate on a psychological level, behavioural manipulation methods may be used.

PNES is often the result of traumatic psychological experiences. Sometimes the experiences themselves are forgotten, but their impact remains. PNES is a real condition that is a response to very real stress. People with PNES are not faking their seizures.

How is PNES diagnosed?

EEG video monitoring is the most reliable way to diagnose PNES since these seizures are not associated with a spike and wave pattern on the EEG.

How is PNES treated?

PNES is not treatable with Anti-Seizure Medications. However, it is effectively treated by specialists trained in psychological issues, including psychiatrists, psychologists, and clinical social workers. Some treatments include:

- Psychotherapy

- Stress-reduction techniques (relaxation, bio-feedback)

- Personal support

With proper treatment, 60-70% of adults with PNES will eventually stop having seizures. The success rate is even higher in children and adolescents. Early diagnosis is an important factor in successful treatment.

If you or your loved one has been diagnosed with PNES – call your local Epilepsy Community Agency for guidance on support programs in your community.

Reprinted in part from Epilepsy Ontario.

Seizure First Aid Video

Seizures manifest in several different ways due to the diverse types of seizures that can occur. A person might have a blank stare, pick at objects, flutter their eyes, or convulse. You may not even notice that someone is having a seizure at all! Seizures are rarely a medical emergency, so most of the time you simply need to follow these steps:

- 1. Stay Calm

- Most often, a seizure will run its course and end naturally within a few minutes.

- 2. Time it

- If you know that the person has epilepsy or a seizure disorder and the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes or repeats without full recovery between seizures, call 911.

- Check for medical alert information. It is often located on a bracelet, necklace, cellphone, or in a wallet. If the person has epilepsy or a seizure disorder, having a seizure may not always be a medical emergency.

- Call 911 if the person is pregnant, has diabetes, is injured from the seizure, if the seizure occurs in water, or if regular breathing does not return after the seizure has ended.

- Call 911 if you are not sure the person has epilepsy or a seizure disorder.

- If you know that the person has epilepsy or a seizure disorder and the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes or repeats without full recovery between seizures, call 911.

- 3. Protect from injury

- Move sharp objects out of the way.

- If the person falls to the ground, roll them onto their side and place something soft under their head.

- If the person wanders about, stay by their side and gently steer them away from danger (i.e. traffic, stairs, water).

- When the seizure ends, provide reassurance and stay with the person if they are confused.

*Do not restrain the person.

*Never put anything in the person’s mouth (the person will not swallow their tongue, and the object in the mouth may cause unwanted injuries).

- It is also a good idea to include a downloadable and printable copy of the Seizure First Aid poster for anyone to paste around their house/room/workplace as a reminder.

- To download and print a copy of the seizure first aid poster click here.

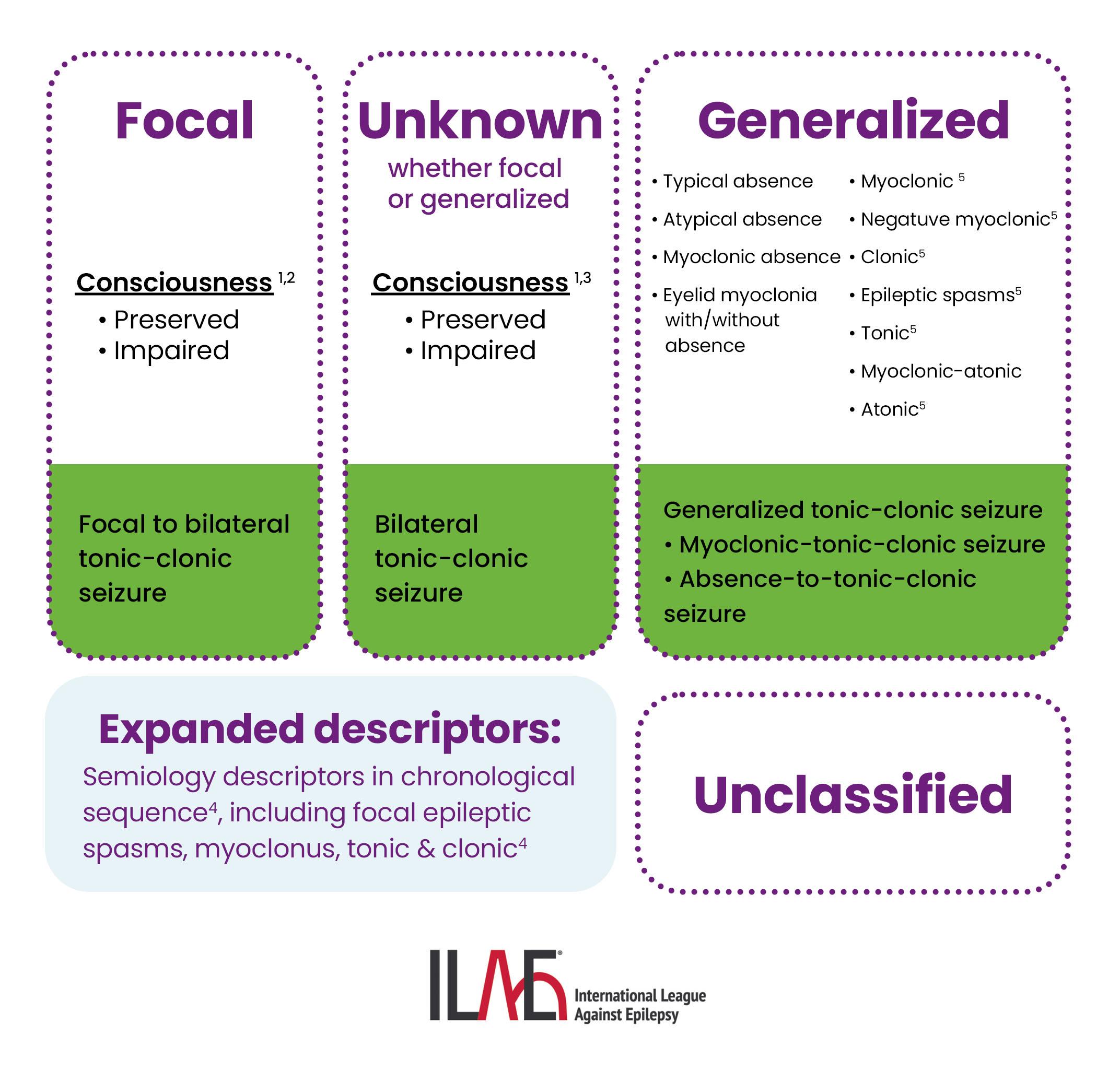

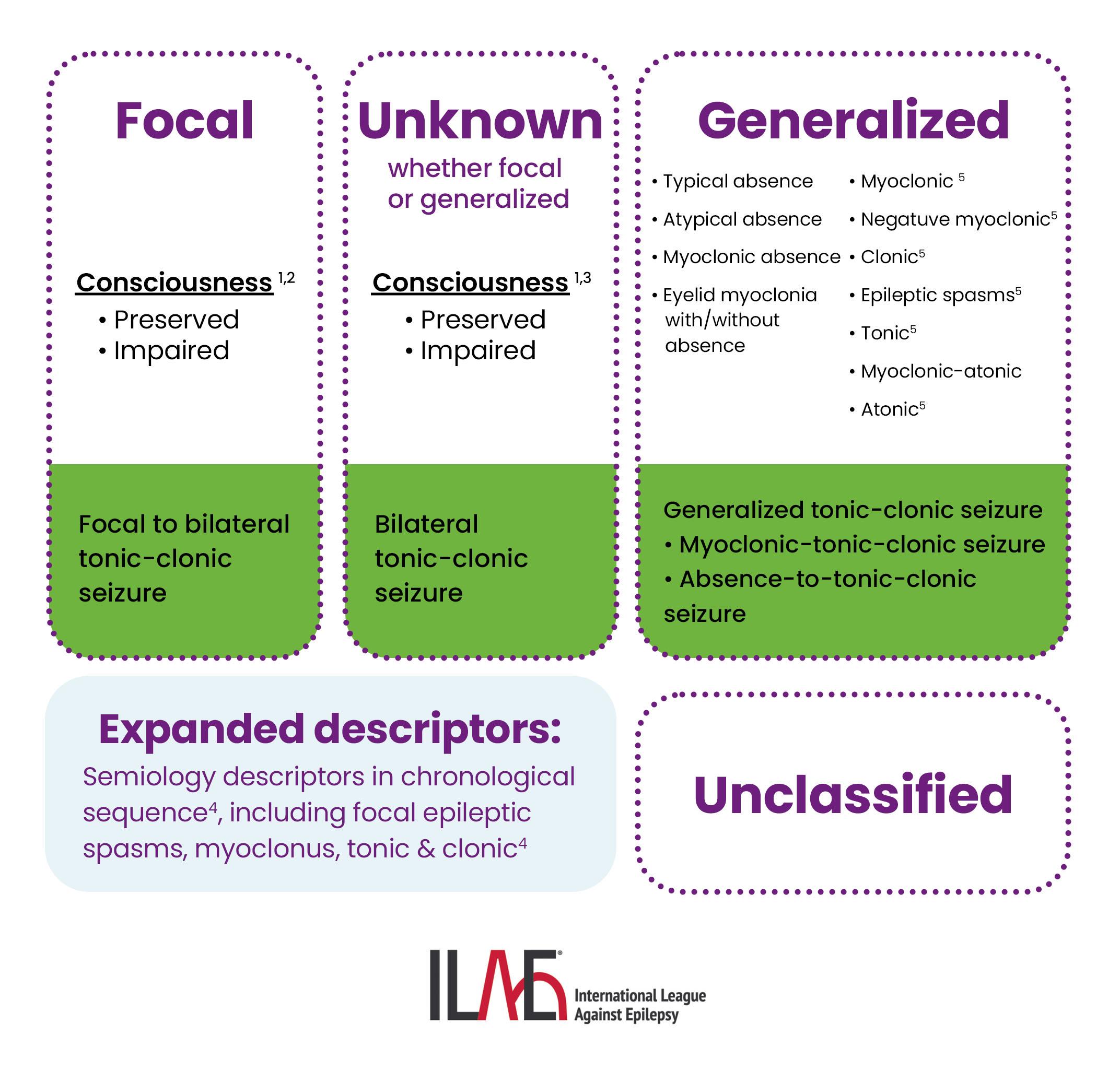

Seizure Types

Table of Contents

- Generalized Seizures

- Focal Seizures

- Unknown Seizures

- Unclassified Seizures

A seizure in the brain is caused when neurons in the brain misfire. Not all misfiring neurons cross the same area of the brain. For this reason, not all seizures look the same. There are several different types of seizures and types of epilepsy.

There are four major groups of seizures.

- Generalized (G)

- Focal (F)

- Unknown whether focal or generalized (U)

- Unclassified

Classification of Seizure Types

Epilepsia, Volume: 66, Issue: 6, Pages: 1804-1823, First published: 23 April 2025, DOI: (10.1111/epi.18338)

1) Generalized Onset

If a misfiring neuron crosses both hemispheres of the brain, we call this a generalized seizure. In a generalized seizure, the person will lose consciousness. Generalized seizures could have observable or non-observable (absence) manifestations affecting various systems of our body. Some people experience auras (focal preserved consciousness seizures) preceding a generalized seizure.

Types of Generalized Seizures

Tonic-clonic

Tonic-clonic (previously known as grand mal seizure or convulsion) is a type of generalized seizure that the person loses consciousness right from the beginning of the seizure. This seizure causes the person to initially become stiff (tonic phase). This is followed by a second phase in which the person’s body exhibits repetitive, rhythmical jerking and twitching movements (clonic phases). The person will regain consciousness slowly. These seizures last one to three minutes but may last up to five minutes. A tonic-clonic seizure may occur after a focal seizure (focal to bilateral tonic-clonic) or occur without warning. Tonic-clonic seizures in childhood could be outgrown in some cases. With the guidance of a doctor, some people may be able to slowly come off medicine if they were seizure-free for a year or two while taking a medicine.

Symptoms

- The person may suddenly fall to the ground or slump over

- Groaning or crying sounds

- Frothing at the mouth

- Bleeding of tongue

- Irregular breathing

- Bluish or gray skin color

- Urination and/or defecation (after seizure)

- Vomiting (after seizure)

First aid (for tonic-clonic seizures)

- If the seizure lasts more than 5 minutes or repeats without full recovery between seizures, call 911.

- Call 911 if the person is pregnant, has diabetes, is injured from the seizure, if the seizure occurs in water or if you are not sure if the person has epilepsy or a seizure disorder.

- Move sharp objects out of the way.

- If the person falls to the ground, roll them onto their side and place something soft under their head.

- When the seizure ends, provide reassurance and stay with the person if they are confused.

- Do not restrain the person.

- Never put anything in the person’s mouth.

After the seizure, the person will need to rest. It might be difficult to wake him/her or get any response from him/her during this time. After a seizure, the person may feel fatigue, confusion, and disorientation, which may last from five minutes to several hours or even days. Rarely does this disorientation last for more than two weeks. The person may fall asleep or gradually become less confused until full consciousness is regained. They may have a headache once they regain consciousness. There is no evidence that tonic-clonic seizures cause mental retardation or brain damage.

Atonic

An atonic seizure is sometimes called a “drop attack” or “drop seizure”. The seizure involves a sudden loss of muscle tone. A part or the whole body may become limp. Typically, these seizures last for a few seconds. There tends to be no warning, so the seizures can be dangerous because of injury. Head protection (helmet) or other protective gear may be used. The seizure usually lasts less than 15 seconds. After an atonic seizure, the person may or may not be confused. Often, the person can resume their daily activity relatively fast, but he/she may need to rest. An atonic seizure may be focal atonic seizure with observable manifestations where the seizure starts in one part of the brain with a loss of tone in one part of the body. It may also be a generalized atonic seizure where the seizure affects both sides of the brain.

Symptoms

- Falling or almost falling down

- Dropping objects

- Nodding the head involuntarily

Who is at risk?

- Atonic seizures usually start in childhood and may last until adulthood

First Aid

- Treat small injuries with first aid and seek medical help for more serious injuries

Myoclonic

The myoclonic seizures with observable manifestations are brief, shock-like jerks of a muscle or a group of muscles. Usually they don’t last more than a second or two. There can be just one, but sometimes many occur within a short time.

- People who do not have epilepsy sometimes experience a sudden jerk of the body when they are falling asleep. This is common and is known as benign nocturnal myoclonus. It is not an epilepsy-related seizure.

First Aid:

- If the person was injured, perform basic first aid (cuts, bruises) or seek emergency medical help for more serious injuries.

Generalized Seizures with Non-Observable Manifestations

Absence Seizures

Absence seizures were formally known as petit mal. This seizure is often referred to as a ‘staring spell’ or ‘blank stare’. It is often mistaken for daydreaming or inattention, and are so brief that they are often unnoticed. In an absence seizure, the person will temporarily lose consciousness. The epileptic activity occurs throughout the entire brain, as it is a generalized seizure. It is a milder type of activity and the seizure is short – maybe as short as 2 – 20 seconds. As such, after the seizure, the person has no memory of it. Absence seizures often affect children. Special care should be taken to ensure that the child is not missing educational information during his/her seizures.

First Aid

After the seizure, explain to the person that they just had a seizure and inform them of anything that they missed.

Typical Absence Seizures

During typical absence seizures, the person suddenly stops and the person may appear to be staring off into space usually with a blank look. The person’s eyes may turn upwards and the eyelids may flutter. The seizures usually last less than 10 seconds.

Atypical Absence Seizures

Atypical absence seizures often last longer, have a slower onset and offset, and exhibit different symptoms. These seizures also begin with the person staring off into space, usually with a blank look. These seizures usually last up to 20 seconds or more. Change in muscle tone and these movements may occur:

- Repetitive blinking that may appear to be fluttering of the eyelids

- Smacking lips and chewing motions

- Hand motions (rubbing fingers together)

2) Focal Onset Seizures

General Info

Focal seizures (previously known as partial seizures) can occur when the seizures start in neurons in one hemisphere or when one part of the brain misfires. Focal seizures can originate within any lobe of the brain – causing frontal lobe seizures, temporal lobe seizures, parietal lobe seizures, insular seizures, occipital seizures or a combination of brain lobes may be involved. There are two types of focal seizures:

- focal preserved consciousness seizure

- focal impaired consciousness seizure.

Sometimes, these seizures may result in focal-to-bilateral tonic-clonic seizures while some may exist on their own.

Common Symptoms:

Observable manifestations

- Jerking (clonic)

- Limp or weak muscles (atonic)

- Tense or rigid muscles (tonic)

- Brief muscle twitching (myoclonus)

- Epileptic spasms

- Automatisms or repeated automatic movements (clapping, rubbing hands, lip-smacking, chewing, running)

- Lack of movement (behaviour arrest)

Non-observable manifestations

- Changes in thinking or cognition

Autonomic (non-motor): This has sometimes been referred to as abdominal epilepsy

- Abdominal discomfort or nausea which may rise into the throat (epigastric rising)

- Stomach pain

- The rumbling sounds of gas moving in the intestines (borborygmic)

- Belching

- Flatulence

- Vomiting

- Pallor

- Flushing

- Sweating

- Hair standing on end (piloerection)

- Dilation of the pupils

- Alterations in heart rate and respiration

- Sexual arousal

- Penile erection

Emotional

- One feels emotions, often fear, but sometimes sadness, anger, or joy

Sensory

- Some simple partial seizures consist of a sensory experience. The person may:

- See lights

- Hear a buzzing sound

- Feel tingling or numbness in a part of the body

- Have a bad smell or a bad taste

- Have a funny feeling in the pit of the stomach

Have a choking sensation

Focal Preserved Consciousness Seizures (previously known as Focal Onset Aware Seizures)

Focal Preserved Consciousness Seizures (previously known as focal onset aware seizures or simple partial seizures) the person is awake and aware during the seizure, but will be unable to control various body movements. People experiencing a focal preserved consciousness seizure may be able to talk and answer questions. They will remember what happened during the seizure. If there are no convulsions, they may not be obvious to the onlooker. Focal preserved consciousness seizures usually last two to 10 seconds, although they may last longer.

Who is at risk?

- Although it is possible for anyone to experience focal preserved consciousness seizures, there is elevated risk for people who have had head trauma, brain infection, stroke, or brain tumour.

First aid

- Comfort and reassure the person if the person feels confused following the focal preserved consciousness seizure. Usually, the person should be able to return to their normal task.

Focal Impaired Consciousness Seizures (previously known as Focal Onset Impaired Awareness Seizures)

Focal Impaired Consciousness Seizures (previously known as focal onset impaired awareness, focal dyscognitive, complex partial, psychomotor, or temporal lobe seizures), a focal impaired consciousness seizure often occurs after a focal preserved consciousness seizure originating in the temporal lobe. Some lead to generalized tonic-clonic seizures, but during the focal impaired consciousness seizure, the individual will not fall to the ground and shake. These seizures usually last around one to two minutes. They might have an aura (which is a type of focal preserved consciousness seizure). Everyone will experience focal impaired consciousness seizures differently. Someone experiencing a focal impaired consciousness seizure (previously known as focal onset impaired awareness or complex partial seizure) may become frightened and try to run and struggle. The seizure usually lasts about two to four minutes. In some people, focal impaired consciousness seizures can lead to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, where the seizures spread to both sides of the brain. These seizures are called focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures.

Where do these seizures usually originate?

- Temporal lobe is the most common site

- Frontal lobe of the brain

3) Unknown onset

4) Unclassified

Complete lack of information to be place in any other category.

TERMS

1. Automatisms

Automatisms

Are “inappropriate” automatic behaviours from a focal impaired consciousness seizure that are any of the following:

- Chewing movements

- Uncoordinated activity

- Meaningless bits of behaviour that appear random and clumsy including:

- Picking at their clothes or trying to remove them

- Walking about aimlessly

- Picking up things

- Mumbling

2. Postictal State

A postictal state occurs at the end of an epileptic seizure when an individual is recovering. It may not always be clear when a postictal state has begun after a seizure. It will manifest itself differently depending on the type of seizure, and the type of brain affected by the particular seizure. The person may need to rest for a while or may be able to resume activities very soon after having a seizure. Thus, the length of a postictal state and the types of activities that take place during a postictal state may vary. It may be difficult to wake a person or get any response from him/her during a postictal state. The person may feel fatigue, confusion, and disorientation, which may last from five minutes to several hours or even days. Rarely, this disorientation may last up to two weeks. The person may even fall asleep, or gradually become less confused until full consciousness is regained. S/he may have a headache once s/he regains consciousness. It is important to observe the length of a postictal state to determine when it is safe for a person to resume normal activities. At the end of a postictal state, the individual enters an interictal state, which describes the period between two seizures.

3. Aura

An aura is a form of focal preserved consciousness seizure and is experienced as peculiar sensory or motor phenomenom before the onset of another seizure. They are a good indication that a generalized seizure (widespread seizure activity in both hemispheres of the brain) is about to occur. Auras may also lead to focal impaired consciousness seizures. It is helpful to teach a child with epilepsy about auras to help them take quick precautions to ensure safety and avoid potentially harmful situations.

Common aura descriptions:

- Butterflies in the stomach

- Flashes of light

- Odd noises (e.g. buzzing in the ear)

- Strange smells (e.g. burnt toast, rotten eggs)

- A powerful emotion

- Dizziness

- Tingling or burning sensation

- Sudden jerky movement of a limb

4. Provoked Seizure

A seizure that results from a change in body homeostasis – changes in temperature, blood glucose or blood sodium levels can cause a provoked seizure. If someone has repeated seizures, but the seizures are always provoked by physiological change (such as fever) they are not considered to have a neurological disorder.

Status Epilepticus

Seizures usually end naturally after a few seconds or minutes, but on rare occasions, a seizure doesn’t stop. When a seizure goes on longer than 30 minutes or repeats in a series without recovery between seizures, the person may be experiencing status epilepticus. The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) describes status epilepticus as a condition resulting either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms, which lead to abnormally, prolonged seizures. It is a condition, which can have long-term consequences, including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of seizures. This state of continuous seizure activity can happen with any type of seizure. Status epilepticus is considered a medical emergency and can be life-threatening.

Reference:

Trinka, E., Cock, H., Hesdorffer, D., Rossetti, A. O., Scheffer, I. E., Shinnar, S., … Lowenstein, D.

- (2015). A definition and classification of status epilepticus – Report of the ILAE task force on classification of status epilepticus. Epilepsia, 56, 1515-1523.

SUDEP

Sudden Unexplained Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) refers to the unexpected death of a seemingly healthy person with epilepsy, where no cause of death can be found. Rather than pertaining to a specific disease or condition, it is used to denote a category to which these types of unexplained deaths are assigned.

What causes SUDEP?

The precise mechanism, or cause, of death, is as yet, not understood. Most sudden deaths of people with epilepsy are unwitnessed and this makes it difficult to determine what, exactly, occurs in the last moments of life. By definition, the post-mortem does not reveal a cause of death, suggesting that the terminal event is due to a disturbance of function, not structure. Most frequently, but not always, there is evidence for seizure activity prior to death and recent studies strongly support a close relationship between seizure episodes (especially generalized convulsions) and SUDEP.

Various potential mechanisms have been proposed and these mainly involve a disruption to the cardiac and/or respiratory systems. It is unknown whether mechanisms are jointly or severally responsible, what leads to the fatal cardiac event and/or the cessation of breathing, what role the brain and/or seizure plays in the whole process, or indeed, whether the same events trigger SUDEP in each person.

Risk factors for SUDEP

Without a known cause, it is not feasible to accurately determine whether or not an individual may be predisposed to SUDEP. However, investigations of SUDEP circumstances have identified several associated, or contributory, factors that indicate some individuals are at higher risk.

The factors most consistently identified in case studies include those which are deemed non-modifiable, such as early onset of epilepsy and young adult age and those which are deemed modifiable with the potential to lower SUDEP risk. These include, but are not limited to, frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures, poor compliance with the anti-epileptic drug (AED) regime and the number of different types of AEDs used.

What is the incidence of SUDEP?

SUDEP is estimated to account for up to 18% of all deaths in patients with epilepsy. Consistent and comparable data on the incidence of SUDEP and its risk factors is proving difficult to ascertain. This is due to differences in research methodologies (including the definition of SUDEP, study type, and reference populations) and inevitable methodological limitations. Most studies are restricted to small sample sizes and select epilepsy groups (such as tertiary care clinics or residential homes) because of the relatively rare incidence of SUDEP in the population and the impracticality of studying large numbers of individuals with epilepsy from diagnosis to death. The alternative research approach, conducting retrospective studies of those identified as having died from SUDEP, is hampered by the apparent underuse of the term SUDEP as a cause of death on death certificates, as found in the UK (Langan et. al. 2002) and the USA (Schraeder et. al. 2006). Instead, the cause may be registered as, for example, ‘respiratory failure’ or ‘unascertained’ and would thereby be erroneously excluded from SUDEP case studies or statistics. Epidemiological data from research conducted to date has demonstrated substantial variance in incidence depending on the epilepsy cohort studied. This has been shown to range from 0.09 per 1000 person-years in a community-based study (Lhatoo et al 2001) to 9 per 1000 person-years in candidates for epilepsy surgery (Dasheiff 1991).

Minimizing the risk of SUDEP

In the current absence of a proven SUDEP prevention method, the recommended approach is to attempt to keep modifiable contributory factors to a minimum. As research indicates that SUDEP is largely a seizure-related phenomenon, optimization of seizure control is highly important. Recommendations to achieve this include:

- seeking regular medical consultation to re-evaluate epilepsy diagnosis, review medication and the possibility of new treatments, discuss implications of lifestyle changes, etc;

- maintaining good adherence/compliance with medication regime, and

- identifying possible triggers for seizures, and determining an effective strategy for keeping these to a minimum. For example, maintaining regular and adequate sleep patterns or learning ways to better manage stress.

It is also prudent for family, friends, and caregivers to be informed of what to do during and following a seizure. This includes knowledge of the recovery position and cardiopulmonary resuscitation techniques, as well as the necessity of calling an ambulance if the seizure lasts for more than 5 minutes or repeats without full recovery, and of staying with a person for 15-20 minutes after the seizure to ensure that recovery continues.

Reprinted in part from SUDEP Aware.

Treatments

Medication

The most common treatment for epilepsy is a class of drugs known as anti-seizure medication/ anti-seizure drugs (ASD). In general, the drugs that are used to treat epilepsy are designed to dampen or decrease the excitability of brain cells. This raises the seizure threshold and makes it less likely that a seizure will occur. Therefore, some of the side effects of these medications are related to the drug’s action on brain cells and can interfere with normal brain function. Side effects may be more pronounced when a medication is first introduced and may subside as the person’s brain adjusts to the drug. A person who is taking more than one ASD has a higher likelihood of experiencing side effects than someone taking a single medication.

An individual’s epilepsy may be referred to as drug-resistant epilepsy when two appropriately selected and administered anti-seizure drugs (ASDs) do not control the seizures effectively. Previously, drug-resistant epilepsy was called medically intractable, refractory, and pharmacoresistant epilepsy. For drug-resistant epilepsy, there are other treatment options available that can be very successful, including but not limited to brain surgery, nerve and brain stimulators, and dietary treatments.

NEVER stop any anti-seizure medication without talking to your health care provider first. This can be very dangerous.

ALWAYS talk to your health care provider before changing your medication or dosage. This includes switching between name brands and generic drugs. Making changes to your medication routine without medical supervision can lead to unexpected seizures or side effects.

ALWAYS talk to your health care provider about the other medications, supplements, and herbal remedies you are taking. These may alter the effectiveness of your anti-seizure medication.

TIP: Some medications need to be monitored with blood tests for your health and safety. Before starting a new anti-seizure medication, ask your health care provider if you need to get blood tests and if so, how often.

Although 70% of people with epilepsy will obtain excellent seizure control with medication(s), the other 30% will not. However, there are other treatment options available that can be very successful including brain surgery, nerve and brain stimulators, and dietary treatments.

Tips for Remembering Your Medication:

- Take your medication as part of your daily routine – always at the same time, and in conjunction with other regular, daily activities. This will help you remember to take your medication, it will become an automatic part of your daily routine.

- Set an alarm to remind yourself to take your medication.

- Use a pillbox with compartments for each day of the week so you can track if you’ve taken that day’s dosage.

- There are also apps for mobile devices that will help you remember to take your medication.

Questions for Your Health Care Provider:

- What side effects should I expect?

- Is there a risk of allergic reactions to the medication I am taking? If so, what are the signs of an allergic reaction and what should I do if they appear?

- How will this medication interact with other medications, herbal remedies, or supplements I’m taking?

- What do I do if I miss a dose?

Women and Anti-seizure Medications

Some anti-seizure medications can reduce the effectiveness of oral contraception (the birth control pill). If you are taking the birth control pill, discuss your medication options with your health care provider. If you are considering getting pregnant, are pregnant, or interested in breastfeeding, work with your health care provider to find an anti-seizure medication that is safe for you and your baby.

For more information about anti-seizure medications and women, please see our Women and Epilepsy resource sheet.

Brain Surgery

People living with epilepsy may be eligible for a variety of brain surgeries. Surgery may involve removing the part of the brain (resective surgery) where the seizures originate or it may involve cutting nerve fibers to prevent seizures from spreading from one side of the brain to the other.

The most common type of epilepsy surgery is performed on patients with focal epilepsy, which means their seizures are coming from a specific location in the brain. Surgery for this type of epilepsy usually involves removing the part of the brain responsible for the patient’s seizures. Surprisingly, many parts of the brain can be removed without causing any problems, and fortunately, most cases of focal epilepsy occur in these non-essential areas. However, all cases are treated individually and the risks and benefits of surgery need to be weighed thoroughly for each patient.

Patients being considered for epilepsy surgery are normally seen first by a neurologist who specializes in epilepsy. All patients have an MRI scan and a test called an electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures the brain’s electrical activity. Next, patients are admitted to a special ward in the hospital that is used to monitor their seizures. They are hooked up to an EEG and monitored by a camera 24-hours a day. The goal is to capture seizures on video and for the neurologist to see what the brain activity looks like at the same time. Many other tests may be done during this hospital stay, including additional brain scans and psychological testing. The admission to the epilepsy unit lasts about a week but can be longer in some circumstances. This hospital admission is often memorable and eye opening for patients as they meet other people with epilepsy and share stories with them and their families. They often realize that they are not alone.

After the hospital admission, the doctors meet to discuss the test results to decide if a patient is eligible for surgery. Occasionally, additional tests are required in order to reach a final decision. In about half of patients, it is decided that a more detailed EEG is required, one with intracranial electrodes. Unlike the regular EEG, which uses electrodes on the scalp, these electrodes are surgically placed inside the skull and may be either on the brain (called subdural electrodes) or in the brain (called depth electrodes). It is during this stage that patients will meet their surgeon and can discuss the details of the procedure and what risks may be involved. Patients are then brought back into the hospital for an operation to insert the electrodes. After surgery, they stay in the same epilepsy unit as before, only this time it is often a longer stay, lasting a week or two or even longer. Once the intracranial EEG is completed, the electrodes are removed and the patient is discharged. The doctors will then meet again to discuss the results of the tests and make a final decision about surgery.

Once a final decision is made about surgery, the doctor carefully chosen surgery candidates have about an 80% chance of being seizure-free after surgery.

Click here for more information.

Nerve and Brain Stimulators

People who are not candidates for resective brain surgery may have other surgical treatment options. For example, the Vagal Nerve Stimulator (VNS) is a battery-powered device that is surgically implanted under the skin in the chest and delivers electrical impulses to the vagal nerve in the neck.

Learn more information about VNS Therapy: here

Learn more about VNS Therapy- AspireSR : here

Ketogenic Diet

A ketogenic diet is a high fat, low protein, low carbohydrate diet. This treatment is used primarily in children whose seizures are not well-controlled with medication and when resective surgery is not an option. There are also variations of this diet that have been used successfully in adults. The ketogenic diet is a medical treatment and should only be implemented under a doctor’s supervision.

Click here for more information.

Complementary Therapies

Some people with epilepsy find it helpful to incorporate complementary therapies in conjunction with their traditional medical therapy. Anti-seizure medication is the primary treatment for epilepsy, but 30% of people with epilepsy will not gain seizure-control with medication alone. In these cases, complementary therapies can help alleviate seizures when administered in addition to anti-seizure drugs.

Complementary therapies include acupuncture, chiropractic care, massage therapy, relaxation, guided imagery, biofeedback, aromatherapy, yoga, therapeutic touch, homeopathy and diet. These are unconventional or non-medical therapies that tend to focus on the integration of the body, mind and spirit, sometimes referred to as the holistic model.

TIP: Always consult with your health care provider before adding complementary therapies to your epilepsy treatment routine.

Chemicals, including herbs, can affect the way anti-seizure drugs work. Your health care provider can advise you about the impact of the complementary therapy on your medication as well as any safety precautions you should take when trying out other complementary therapies such as yoga.

Are complementary therapies effective in treating epilepsy?

There has not been much research looking into complementary therapies for epilepsy, so there is little scientific evidence of their effectiveness. However, some people who have tried complementary treatments have felt that these have helped their epilepsy and improved their quality of life.

Reducing stress can reduce seizures in some people, and complementary therapies that include stress-reduction techniques can help some people better control their seizures. Furthermore, the greater involvement of the person with epilepsy in his or her own seizure management through these therapies can be positive in itself.

For more information on complementary therapy for epilepsy click here

Medical Marijuana

Implications for People Living with Epilepsy

New evidence has been found in the benefits of using medical marijuana as a treatment for epilepsy. Here are some facts about this new treatment.

Cost:

- Varies depending on:

- Strain and level of THC and CBD

- Oil vs. dried plant

- Financial need determined by a healthcare provider

- Although most health insurance plans do not cover the purchase of Marijuana products (Emerald Health Botanicals, 2016), some companies offer compassionate pricing programs, where marijuana products can be subsidized based on financial and medical need (Delta 9 Bio-Tech, 2014).

Side Effects/Long-Term Use:

- Factual information on side effects (especially long-term use side effects) is very limited as there is such a wide variety of side effects that are felt depending on the person.

- The complete Health Canada consumer information sheet can be found at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-use-marijuana/licensed-producers/consumer-information-cannabis-marihuana-marijuana.html (Canada, 2016).

Cannabis Products Should NOT Be Used When:

- The user is under the age of 25.

- Allergic to cannabinoids or smoke.

- Have a liver, kidney, heart, or lung disease.

- Have a personal or family history of mental disorders.

- Are pregnant or breastfeeding.

- A man or woman is planning on having children in the near future.

- Have a history of drug/alcohol abuse or dependence.

To Obtain/Produce Marijuana for Medical Purposes, One Must:

- First, consult with a medical provider.

- Obtain a medical document from your medical provider including your information, practitioner information, and dosing information (the complete list of information can be found at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/drugs-health-products/understanding-new-access-to-cannabis-for-medical-purposes-regulations.html#a2).

- Register as a client under a licenced producer, where you will be asked to submit your medical document from your medical provider. After approval, you will be authorized to purchase cannabis products (visit https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-use-marijuana/licensed-producers/authorized-licensed-producers-medical-purposes.html for details).

- Cannabis will be sent directly to you.

- For an individual to be able to produce a limited supply of marijuana for medical purposes, one must first submit an application to register under Health Canada.

- Once approved, an individual will be given a certificate, and specific guidelines in which production, use and possession must follow.

- One may use this certification to obtain starting materials (plants/seeds) from a licenced producer (Health Canada, 2017).

What is CBD?

- Cannabidiol (CBD) is a type of chemical found in cannabis plants, called a cannabinoid (chemicals that react with receptors within the body of the consumer) (Campbell, Phillips, & Manasco, 2017).

- Non psychoactive in nature (unlike other cannabinoids like THC) (Campbell, Phillips, & Manasco, 2017).

- Does not alter the mind or behaviour of the person using it – a.k.a. does not produce a “high” like THC might (Devinsky et al, 2014) because it does not activate the receptors responsible for these characteristics.

- CBD may be effective in the treatment of epilepsy through the action of degrading the endocannabinoid, Anandamide is a chemical that is thought to play a role in seizures, as it has the potential to excite neurons, thus inducing the seizure (Campbell, Phillips, & Manasco, 2017).

- In other words, by acting against this chemical, CBD is thought to prevent the firing of neurons that send someone into a seizure (Devinsky et al, 2014).

Cannabis Use: Children Vs Adults

- There is quite little research on the effects of cannabis on children thus increasing hesitation when giving it to the younger population.

- In general, it is believed that cannabis use in those under the age of 25 can impair brain and central nervous system functioning, as the brain is still developing during these crucial years (Weir, 2015).

- Because of the limited concrete evidence in the effects of CBD on the mind, there is much hesitation in prescribing it to a still-developing patient (Weir, 2015).

- According to the American Psychological Association, short-term use of cannabis has shown to cause impairments to functions such as:

- Attention

- Memory

- Learning

- Decision-making (Weir, 2015)

- According to the American Psychological Association, long-term use of cannabis has shown to cause long-term problems such as:

- Poor school performance

- Higher dropout rates

- Increased welfare dependence

- Greater chance of unemployment (Weir, 2015)

- It should be noted, however, that there may be external factors contributing to these patterns.

- The more variations in treatments (edible products, hemp oil, hybrid breeds of the plant, etc.) become available, the greyer the effects of cannabis use on children becomes.

- As of right now, it is generally accepted that in Canada, unless other conventional forms of medicine fail, those under the age of 25 should not be prescribed marijuana for medical purposes, as these potential side effects are not worth the risk otherwise (The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, 2016).

- One counter argument presented by Orrin Devinsky, the director of the NYU Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, states that all this being said, we also do not know the long-term effects of antiepileptic drugs on the same developing brains (Patel, 2017) therefore how can we criticize cannabis in children to such a degree.

References

Campbell, C. T., Phillips, M. S., & Manasco, K. (2017). Cannabinoids in Pediatrics. The

Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 22(3), 176–185. doi: 10.583/1551-6776-22.3.176

Canada. Health Canada. (2016). Consumer Information – Cannabis (Marihuana, marijuana).

(Pub. : 160110). Ottawa: Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/medical-use-marijuana/licensed-producers/consumer-information-cannabis-marihuana-marijuana.html

Delta 9 Bio-Tech. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.delta9.ca/pricing_policy.html

Devinsky, O., Cilio, M. R., Cross, H., Fernandez-Ruiz, J., French, J., Hill, C., Katz, R., Di

Marzo, V., et al. (2014). Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia, 55(6), 791–802. doi: 10.1111/epi.12631

Emerald Health Botanicals. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.emerald.care/

Health Canada. (2017). Understanding the New Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes

Regulations. In Government of Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/drugs-health-products/understanding-new-access-to-cannabis-for-medical-purposes-regulations.html#a2

Patel, A. (2017). Medical Marijuana and Epilepsy. In Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved from

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. (2016). Marijuana for Medical Purposes.

Toronto: The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario.

Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. American Psychological Association,

46(10) 48.

References:

Kwan, P., Arzimanoglou, A., Berg, A. T., Brodie, M. J., Allen Hauser, W., Mathern, G., … French, J. (2010).

Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia, 6, 1069-77.

Triggers

The following list contains possible triggers of seizures:

Medication

- Not taking one’s anti-epileptic medication

- Other medications that are taken in addition to anti-epileptic medication

Internal Factors

- Stress, excitement, and emotional upset

- This type of over-stimulation may lower the person’s resistance to seizures by affecting sleeping or eating habits

- Boredom

- Research shows that individuals who are happily occupied are less likely to have a seizure.

- Lack of sleep can change the brain’s patterns of electrical activity and can trigger seizures.

- Fevers may make some children more likely to have a seizure.

- Menstrual cycle

- Many women find their seizures increase around this time of their period. This is referred to as catamenial epilepsy and is due to changes in hormone levels, increased fluid retention, and changes in anti-epileptic drug levels in the blood.

External Factors

- Alcohol can affect the rate at which the liver breaks down anti-epileptic medication.

- This may decrease the blood levels of anti-epileptic medications, affecting an individual’s seizure control.